Neolithic

In 6 thousand B.C. almost simultaneously, in different extremities of Europe, a new, neolithic cultural tradition arises, associated with the cultivation of cereals, the grazing of domestic animals (cattle, goats, sheep), the extensive use of ceramics, and permanent dwellings. In central Europe, the Neolithic was associated with the culture of linear-tape ceramics, which for several centuries reached the Atlantic coast of northern France. Another Neolithic culture, La Hoguette, arrived in the eastern regions of France as the successor to the Impresso culture that emerged in the Ibero-Italian region. In the culture of La Hoguette, as in the preceding western version of the culture of impresso, sheep and goat breeding prevailed. There is evidence that around 5100 B.C. in the south of England, milk begins to be consumed and livestock appear – descendants of livestock domesticated in the Aegean region shortly after the Holocene. Apparently, these animals were brought to Britain by representatives of the culture of linear-tape ceramics. Around 4300 B.C. livestock appears in Northern Ireland, and after it appears the red deer.

Since 4500, a set of neolithic traits penetrated into Ireland, including the cultivation of cereals, the culture of building permanent houses (like those that existed at the same time in Scotland) and stone monuments. Sheep, goats, cattle, and cereals were brought in from the southwest of continental Europe, and this stimulated a sharp increase in population. An extensive system of neolithic agrarian fields, perhaps the oldest in the world, has been preserved under the peat layer on the Kade Fields in County Mayo. Consisting of small areas, separated from each other by stone walls, folded dry masonry, these fields were processed for several centuries, approximately between 3500 and 3000 years. B.C. The main crops cultivated here were wheat and barley. Pottery originated at about the same time as agriculture. Ceramics similar to those found in the north of Britain were excavated in Ulster and in Limerick. Typical for this pottery are bowls with a wide neck and a round bottom.

Processes in Britain are in many ways reminiscent of the Neolithic onset in western Europe, for example, in the regions where the culture of La Hoguette or Iberian epicardial culture is spread. Grain crops gradually slow down as they approach northern France, especially since a number of cereals such as wheat were difficult to grow in a cold climate, but instead barley and German rye spread in the north. It can also be assumed that slowing the spread of cereal crops in Ireland, Scotland and Scandinavia is related to aspect DQ2.5 haplotype AH8.1, since this haplotype is associated with susceptibility to the disease caused by wheat protein, type I diabetes and other autoimmune diseases, the spread of which indirectly stimulated the Neolithic.

The most significant characteristic of Neolithic in Ireland was the sudden appearance and sharp spread of megalithic monuments. Human remains are found in most megaliths usually, though not always, cremated, as well as funerary offerings – ceramics, arrowheads, beads, pendants, axes, etc. Currently, about 1,200 megalithic tombs are known in Ireland that can be divided into 4 large groups.

In some regions of Ireland there were shepherd communities, which suggests that some Neolithic inhabitants of Ireland, as in the Mesolithic, continued to maintain their migratory rather than sedentary lifestyle. Apparently, there was a regional specialization: sedentary agriculture prevailed in parts of the regions, and the rest was shepherding.

At the peak of the Neolithic population of Ireland could be from 100 to 200 thousand people. Around the XXV century B.C. there is an economic collapse, and the population decreases for a while.

Copper and Bronze Age (2500-700 BC)

Metallurgy arrives in Ireland with the tradition of bell-shaped cups. Pottery related to this tradition differed sharply from elegant neolithic ceramics with a rounded bottom. Bell-shaped cups are found, for example, in Ross Island in Killarney National Park and are associated with copper mining in these places. Apparently, the appearance of cups is associated with the arrival of speakers of Indo-European languages from Europe, perhaps even one of the branches of Celtic languages.

The copper age began around 2500 B.C. when copper began to be alloyed with tin to make bronze and its products.

Bronze was used to make both weapons and tools. In the archaeological monuments of the Bronze Age, items such as swords, axes, daggers, sword cutters, halberds, awls, drinking utensils, horns (musical instruments) and much more were found. The artisans of Ireland in the Bronze Age were particularly adept at making musical horns, made according to wax models.

Copper, used for the production of bronze, was mined in Ireland, mainly in the south-west, while tin was imported from Cornwall. The earliest known copper mine in Ireland was located on an island of Rossi in the middle of one of the lakes of Killarney in the territory of the modern county of Kerry, where in the period of the XXIV-XIX centuries B.C. Copper mining and processing was carried out. Another well-preserved copper mine, which operated for several centuries in the middle of 2 thousand B.C. was found in Mount Gabriel in County Cork. It is estimated that the total copper production in the mines of Cork and Kerry in the Bronze Age was about 370 tons. Since only 0.2% of this amount comes from bronze artifacts found during excavations, it is assumed that Ireland was a major exporter of copper at the time.

Also in Ireland, native gold is often found. In the Bronze Age begins large-scale processing of gold by Irish prehistoric jewelers. More gold treasures from the Bronze Age are found in Ireland than anywhere else in Europe. Irish gold jewelry was found far enough away from it, right up to the territory of Germany and Scandinavia . In the early stages of the Bronze Age, these decorations consisted of fairly simple crescents and disks made of a thin sheet of gold. Later, the famous Irish twisted necklace appeared: consisting of a metal bar or ribbon, twisted along an axis and then bent in the form of a closed arc. Also in Ireland were made gold earrings, sun discs and lunula.

Small wedge-shaped tombs continued to be built in the Bronze Age, but the Neolithic grand corridor tombs were abandoned forever. By the end of the Bronze Age, cysts appeared for solitary burials: they were a rectangular stone sarcophagus covered with a stone slab and buried shallowly in the ground. Also at this time numerous stone circles (cromlechs) were erected, mainly in Ulster and Munster.

According to genetic research, the Irish are descendants of farmers from the Mediterranean who destroyed the ancient population of the Emerald Isle, as well as the Black Sea coast herders. Black Sea immigrants Indo-Europeans brought their own language and genes of hemochromatosis, as well as genes that allow digesting lactose and drinking milk.

During the Bronze Age, the climate in Ireland deteriorated, and large-scale deforestation occurred. The population of Ireland at the end of the Bronze Age was from 100 to 200 thousand people, that is, about the same as at the end of the Neolithic.

The Iron Age (700 BC – 400 AD)

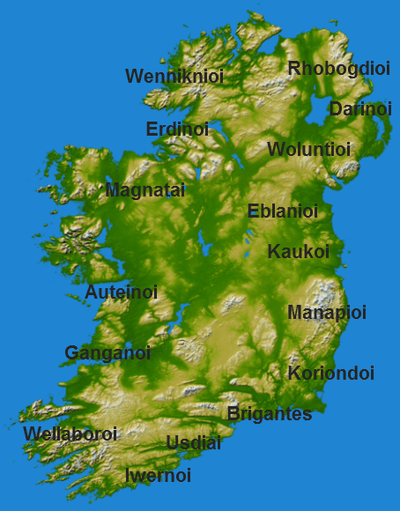

The Irish Iron Age began around VII century B.C. and continued until the Christianization of Ireland, with which writing came into the country and, thus, the prehistoric period ended. Thus, the Irish Iron Age includes a period when the Romans ruled the neighboring island of Britain. The interest of the Romans to the neighboring territory led to the appearance of the earliest written evidence of Ireland (Iverni). The names of the local tribes were recorded in the II century by the geographer Ptolemy – these are Celtic names.

The Celtic languages of Britain and Ireland, despite a number of common features formed within the framework of the island Celtic language union, are divided into two groups: P-Celtic (British) and Q-Celtic languages (Goydel). The first written sources appeared in Ireland proper, Goydel’s languages (Q-Celtic) were spread in it, whereas in Britain – British languages (P-Celtic).

Previously it was assumed that the speakers of Celtic languages first came to Britain and Ireland in the Iron Age, bringing with them characteristic cultures – Hallstatt and then Latent. However, archaeological artifacts indicating a connection with these cultures are very scarce and may indicate either import or cultural links with continental Europe. Clear evidence of the influence of the latent culture appears in Ireland around 300 B.C. in metal products and some stone sculptures, mainly in the northern part of Ireland. It may also indicate that the speakers of the Proto-Gendela language could have arrived in Ireland significantly earlier.

Among the Celtic tribes of Ireland were brigands who were simultaneously the largest tribe of northern and central Britain.

The end of the Iron Age, marked changes in lifestyle occur. In the I — II centuries B.C. there is a sharp decline in population, which is indirectly confirmed by the study of samples of ancient pollen, and in the 3rd — IVth centuries it is again rapidly growing. The reasons for both contraction and growth remain unclear, although it is assumed that population growth could be associated with the so-called “golden age” of Roman Britain in the 3rd — 4th centuries A.D. Archaeological evidence of contacts with Roman Britain either trade or raids on its part is most often found in the north of the modern province of Leinster, with an epicenter in the county of Dublin, to a lesser extent on the coast of Antrim county, and to an even smaller extent in Na Rosa on the north coast of county Donegal and around the lake Carlingford-Loch. The funeral rite as a corpse may also have been brought from Roman Britain and spread to Ireland by the 4th-5th centuries.

Sources:

Dardis GF (1986). “Late Pleistocene glacial lakes in South-central Ulster, Northern Ireland”

Barry, T. (ed.) A History of Settlement in Ireland. (2000) Routledge.

Bradley, R. The Prehistory of Britain and Ireland. (2007) Cambridge University Press.

Coffey, G. Bronze Age in Ireland. (1913)

Driscoll K. The Early Prehistory in the West of Ireland. (2006).

Flanagan L. Ancient Ireland. Life before the Celts . (1998).

Herity, M. and G. Eogan. Ireland in Prehistory . (1996) Routledge.

Thompson, T. Ireland’s Pre-Celtic Archaeological and Anthropological Heritage. (2006) Edwin Mellen Press.

Waddell, J., The Celticization of the West: An Irish Perspective

Waddell, J., The Question of the Celticization of Ireland

Waddell, J., ‘Celts, Celticisation and the Irish Bronze AgePrehistoric Ireland